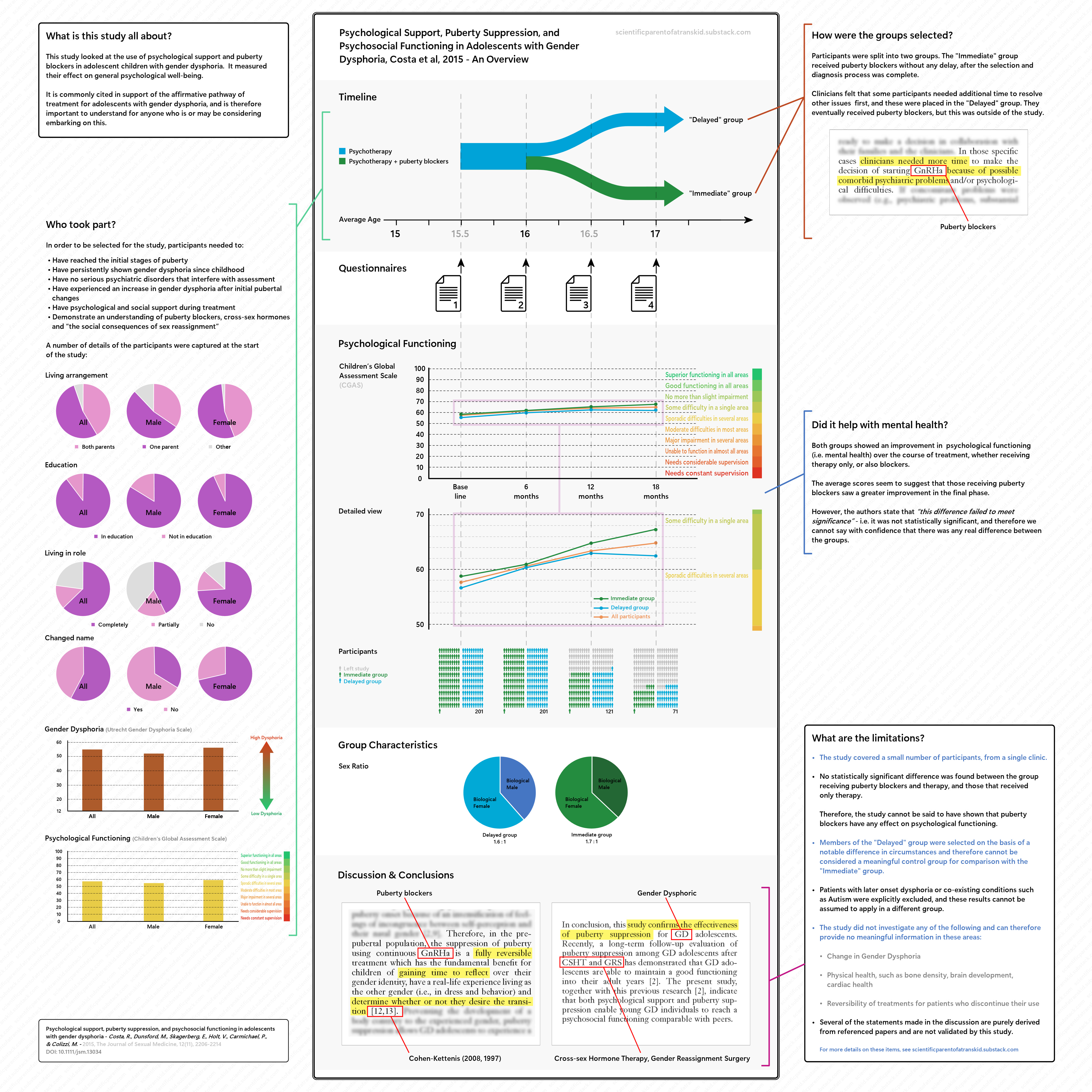

Infographic: A Parent’s Guide to “Psychological Support, Puberty Suppression, and Psychosocial Functioning in Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria”, Costa et al. 2015

Note: I have tried to write this in as plain English as possible, but please see the terminology / definitions section at the end if there are terms that are unclear.

What is this study all about and why would I care?

This study looked at the use of psychological support and puberty blockers in adolescent children with gender dysphoria. It measured their effect on general psychological well-being.

It is commonly cited in support of the affirmative pathway of treatment for adolescents with gender dysphoria, and is therefore important to understand for anyone who is or may be considering embarking on this.

As parents, it is our responsibility to help our child(ren) make informed decisions about these treatments, just like any other medical care. To do that, we need to ask questions like: Is it safe? Is it likely to help my child? What are the risks?

If we are going to answer those questions properly, we need to understand the evidence and be clear on what it does legitimately show and what it does not.

I don’t believe you need a deep knowledge of science to do that and my objective here is to (hopefully) explain this in a way that can be understood by any parent.

This article contains data from the study itself, plus additional analysis based on published reviews and on my own thoughts. Please do evaluate this critically – think for yourself about whether what I am saying is valid and, if there are gaps or mistakes, let me know. I’ll be pleased to hear about them, because I am genuinely pursuing truth and accuracy, and nothing else.

Why an Infographic?

I’m keenly aware that most often this type of information is presented as impenetrable pages of text and numbers. To try and make it easier to digest, I’ve created a visual representation that summarises the information:

Click here for high resolution version of the image

The following is additional information to accompany the graphic, providing further detail and discussion.

Parent Summary

I’ve also written up a detailed “Parent Summary” of this paper, which is intended to be a straight-forward representation of what the authors wrote, without any additional interpretation. Reading it is not at all necessary to understand this piece but it is available here, if you are interested:

Notes on Limitations

1. The study covered a small number of participants, from a single clinic.

The authors note this themselves, saying that “the study sample was relatively small and came from only one clinic”. From the ratios published by the authors and the numbers who completed the study, we can determine the number of participants:

So, for example, if I was the parent of a biologically male child and was helping them consider the risks and benefits of treatment, we would be basing this on the experiences of 13 or 14 relevant individuals, which is not a huge amount.

2. No statistically significant difference was found between the group receiving puberty blockers and therapy, and those that received only therapy.

The authors state themselves that “this difference failed to meet significance” - i.e. it was not statistically significant, and we cannot say with any confidence that there was any real difference between the groups.

The authors suggest this may be due to small sample size but, regardless of the reason, the study cannot therefore be said to have shown that puberty blockers have any specific effect on psychological functioning.

This also calls into question the author’s statement in the study’s conclusions - that the study “confirms the effectiveness of puberty suppression for [gender dysphoric] adolescents.” It is difficult to see how this can be justified when there the results show no clear difference between those who received blockers and those who didn’t.

Similarly, the concluding statement that the results “indicate that both psychological support and puberty suppression enable young [gender dysphoric] individuals to reach a psychosocial functioning comparable with peers” is arguably a bit of a stretch. It is framed in the context of other studies (primarily the Dutch studies) so is perhaps the intention is to position this against the backdrop of existing data but, again, it is hard to see how the results here tell us anything about the effectiveness of puberty blockers.

3. Members of the "Delayed" group were selected on the basis of a notable difference in circumstances and therefore cannot be considered a meaningful control group for comparison with the "Immediate" group.

Even if the results mentioned above had reached the mathematical threshold for statistical significance, there are still fundamental differences between the two groups that make comparing the data questionable.

Of the original participants, the two groups were not selected randomly, but rather on whether the individuals had further issues to resolve before proceeding to puberty blockers. This means there is a fundamental difference in the psychological state of the two groups, and using one as a control group for the other is not valid - the reason being we cannot tell whether any difference is due to the administering of puberty blockers, or due to underlying differences in the groups.

4. Patients with later onset dysphoria or co-existing conditions such as Autism were explicitly excluded, and these results cannot be assumed to apply in a different group.

As the participants were explicitly selected based on having no additional clinical mental health issues, and as having experienced dysphoria since childhood, there is limited validity in applying the conclusions to adolescents who may have other mental health conditions, or who only experienced dysphoria later in life – e.g. when reaching puberty.

This is important to many of the current group of transgender adolescents seeking treatment, as amongst this group there tends to be a high rate of Autism and other mental health conditions, as well as a tendency for gender dysphoria to manifest at a later age.

For example, data published in 2019 showed that 48% of children and young people who were seen by the UK Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) showed autistic traits (Churcher Clarke & Spiliadis, 2019). The same publication refers to a review of referrals to a Finnish clinic over a 2-year period where 65% presented with adolescent-onset gender dysphoria (defined as age 12 and above).

5. The studies did not investigate any of the following and can therefore provide no meaningful information in these areas:

Change in Gender Dysphoria

Physical health, such as bone density, brain development, cardiac health

Reversibility of treatments for patients who discontinue their use

Gender Dysphoria was measured at the outset and not monitored during treatment, and no measurements were taken of effect on physical health.

The cases studied were only those who continued on through treatment, and no data was captured on any participants who discontinued treatment (if there were any).

Given there is no data in these areas, it follows that the studies can offer no meaningful information on these topics.

6. Several of the statements made in the discussion are purely derived from referenced papers and are not validated by this study.

For example, this paragraph:

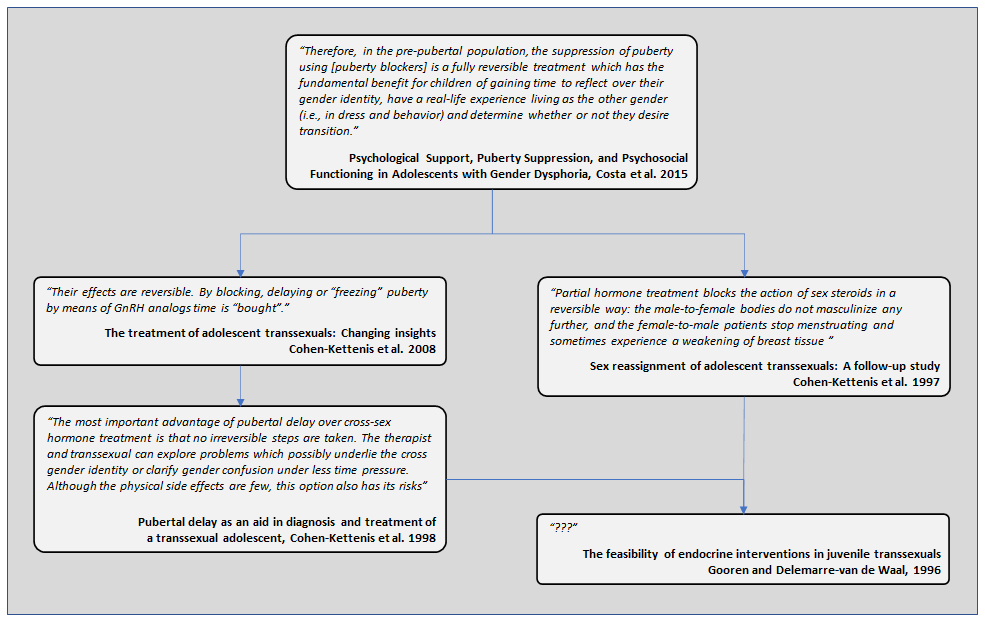

Therefore, in the pre-pubertal population, the suppression of puberty using [puberty blockers] is a fully reversible treatment which has the fundamental benefit for children of gaining time to reflect over their gender identity, have a real-life experience living as the other gender (i.e., in dress and behavior) and determine whether or not they desire transition.

This paper has been used as evidence for the claim that blockers are “fully reversible”. However, as mentioned above, this paper provides no direct evidence to support this, and is quoting other sources to validate this claim.

In fact, the studies it references don’t hold any data either, and they themselves reference other papers and we end up on somewhat of a wild goose chase trying to establish what evidence actually exists for these claims.

I’m still digging, and will be updating this as I find out more but, currently, I have traced the references as follows:

I haven’t been able to source a copy of the 1996 Gooren and Delemarre-van de Waal paper, but both references cited by the authors of this paper seem to trace back to it.

I’ll post an update here if / when I manage to source a copy and can see what it says, but I strongly suspect that most people quoting this study as a source of evidence for the reversibility of puberty blockers in adolescents will not have drilled this far down.

Even putting aside the issues of physical reversibility, there are also major questions over whether the use of puberty blockers in adolescents genuinely ‘buys time’ to consider and make a decision over whether or not continuing on a medicalised path is the right way forward for an individual.

This is the overarching theme of Hannah Barnes’ book (Barnes, 2023), which talks at length about the treatment given to adolescents at GIDS in London. Her book highlights the fact that more or less every single child who starts on puberty blockers continues on to cross-sex hormones and thus the notion that it is a period of contemplation and decision making is highly questionable.

It is possible, I suppose, that the Gooren and Delemarre-van de Waal paper could contain some hitherto unseen evidence that supports this - I’ll update when I am able. If you know of somewhere I can source this paper, please do let me know.

Terminology / Definitions

Gender Dysphoria

There are some differences of opinion on this but in short it means negative feelings about parts of your body that are strongly associated with a particular gender, and a resultant desire to be a different gender.

It is included in the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition) published by the American Psychiatric Association and can be considered a mental disorder on this basis.

Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS)

All care for transgender kids in the UK under the NHS is currently provided by GIDS, the Gender Identity Development Service. At present, this operates mainly from the Tavistock & Portman Trust in London, often referred to as just “The Tavistock”. I say “at present” because a recent independent review (Cass, 2022) led to the recommendation for it to be closed and replaced with regional centres.

Puberty Blockers

These are medications that block the action of key sex hormones in the body and, in adolescent children, have the effect of slowing or stopping the progress of puberty. The medication given is typically a Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone agonist (GnRHa).

Cross-sex Hormones

Sometimes referred to as “Gender Affirming Hormones” these are hormones that are associated with the opposite biological sex, which are given to produce sexual characteristics that are more consistent with that sex – e.g. breasts, facial hair. Typically, this means synthetic Oestrogen for biological males and synthetic Testosterone for females.

Gender Reassignment Surgery

This refers to surgical procedures carried out to modify the patient’s body to give an appearance that is more typical for the desired gender. This usually includes one or more of the following procedures:

Vaginoplasty – removal of the testicles and inverting the penis to create a neo-vagina

Mastectomy – removal of breasts

Hysterectomy – removal of the uterus (womb)

Ovariectomy – removal of ovaries

Metoidioplasty – construction of a neo-penis using existing genital tissue

Phalloplasty – construction of a neo-penis using tissue taken from elsewhere in the body

Utrecht Gender Dysphoria Scale (UGDS)

This is a scale used to rate gender dysphoria, based on two sets of questions, with participants rating statements on a 5-point scale, from “agree completely” to “disagree completely”. The following is the list of questions used along with the scores for each item:

A higher score indicates a higher level of dysphoria, ranging from 12 to 60.

The original paper defining this scale is available here:

https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199702000-00017 (Cohen-Kettenis & van Goozen, 1997)

As this is not accessible without a fee, I have taken the details from a study that references it, here:

This also matches the versions used by the UK Gender Identity Development Service that were provided in this Freedom Of Information request:

https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/request_for_paperwork_for_gids_a

Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS)

This is a general assessment of mental health in a child, with the clinician assessing impact on the patient’s ability to function in day-to-day life. A higher number indicates better global functioning or a lower level of disturbance, with the following bands defined:

The original paper defining this scale is available here:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6639293/ (Shaffer, et al., 1983)

As this is not available without a fee, I have used a copy reproduced here:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272824387_On_the_Children's_Global_Assessment_Scale (Lundh, 2012)

References

Barnes, H. (2023). Time to Think: The Inside Story of the Collapse of the Tavistock’s Gender Service for Children. Swift Press.

Cass, H. (2022). The Cass Review. Retrieved from https://cass.independent-review.uk/

Churcher Clarke, A., & Spiliadis, A. (2019). ‘Taking the lid off the box’: The value of extended clinical assessment for adolescents presenting with gender identity difficulties. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 24(2), 338–352.

Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. & van Goozen, S. H. M. (1997). Sex Reassignment of Adolescent Transsexuals: A Follow-up Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 36(2): 263-71. doi:10.1097/00004583-199702000-00017

Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. & van Goozen, S. H. M. (1998). Pubertal delay as an aid in diagnosis and treatment of a transsexual adolescent. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 7(4): 246-8. doi:10.1007/s007870050073.

Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., van Goozen, S. H. M. Gooren, L. J. G. (2008). The treatment of adolescent transsexuals: changing insights. J Sex Med, 5(8): 1892-7. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00870.x

Gooren, L. & Delemarre-van de Waal, H. (1996). The Feasibility of Endocrine Interventions in Juvenile Transsexuals. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 8(4): 69-74. doi:10.1300/J056v08n04_05

Lundh, A. (2012). On the Children’s Global Assessment Scale. PhD Thesis, Karolinska Institutet.

Schneider, C., Cerwenka, S., Nieder, T. O., Briken, P., Cohen-Kettenis, P., Cuypere, G., . . . Richter-Appelt, H. (2016). Measuring gender dysphoria: A multicenter examination and comparison of the Utrecht gender dysphoria scale and the gender identity/gender dysphoria questionnaire for adolescents and adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45, 551–558.

Shaffer, D., S., G. M., Brasic, J., Ambrosini, P., Fisher, P., Bird, H., & Aluwahlia, S. (1983). A children's global assessment scale (CGAS). Arch Gen Psychiatry, 40(11), 1228-31.

This is an excellent summary. Thank you for the effort. One must ask how the medical institutions and federal government came to the conclusion that puberty blockers are reversible and offer clear benefit. Their reasoning seems to rely on what they want the science to say rather than what does say.

This is an interesting idea and would have been a lot of work! Well done.

Can you upload the image as high res? I’d like to be able to zoom in on sections but when I do the resolution is really poor...