Parent Summary: Psychological Support, Puberty Suppression, and Psychosocial Functioning in Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria

Original authors: Rosalia Costa, Michael Dunsford, Elin Skagerberg, Victoria Holt, Polly Carmichael, Marco Colizzi

DOI: 10.1111/jsm.13034

What is a “Parent Summary”?

My aim in writing this is to present the information contained in the named study in a way that is accessible to a wide range of parents with trans kids, who may not be familiar with digging through formal scientific papers themselves.

I have deliberately avoided expressing any opinion on the content; I am solely aiming to present what the authors say in more straightforward language. It’s not devoid of specialised terminology, but I have tried to make it so everything you need to understand the paper is in one place, with additional data in appendices where I think it is helpful.

I hope that reading this will allow parents to feel confident commenting on the content of a study in further discussion and to assist their child(ren) in making decisions about the treatments discussed.

The full version of the paper can be found at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26556015/ or searched online using the above DOI details.

If you think I’ve missed or misrepresented anything here, please let me know, and I will endeavour to update this article.

Please note: there are certain parts of this study that I personally believe to have significant limitations or inaccuracies - I am not addressing this here, but rather in a separate document, to maintain clarity between my own opinion and recording what the papers themselves say in a clear manner.

What did this study investigate?

This study looked at the use of psychological support and puberty blockers in adolescent children with gender dysphoria. It measured their effect on general psychological well-being.

When and where did it take place?

The study took place at the Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) in London, with participants being recruited between 2010-2014.

How did it work?

Participants were separated into two groups and assessed using questionnaires, filled out at four separate times, 6 months apart:

The questionnaires were completed by the patient themselves, parents and clinicians. The differences between the sets of answers were used to assess the effects of the puberty blockers and psychotherapy.

The delayed group were separated from the immediate group on the basis that the “clinicians needed more time to make the decisions of starting [puberty blockers] because of possible comorbid psychiatric problems and/or psychological difficulties”. Those in the delayed group who subsequently resolved their issues were eventually given blockers, but this was outside of the study.

Who was included?

To be eligible to receive puberty blockers, adolescents would need to:

Have reached the initial stages of puberty

Have persistently shown gender dysphoria since childhood

Have no serious psychiatric disorders that might interfere with assessment

Have experienced an increase in gender dysphoria after initial pubertal changes

Have psychological and social support during treatment

Demonstrate an understanding of puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones and “the social consequences of sex reassignment”

Of 436 candidates referred to GIDS, 201 were accepted on to the study, and 71 were eventually assessed through to the end of the study. The average age at the start of the study was 15.5.

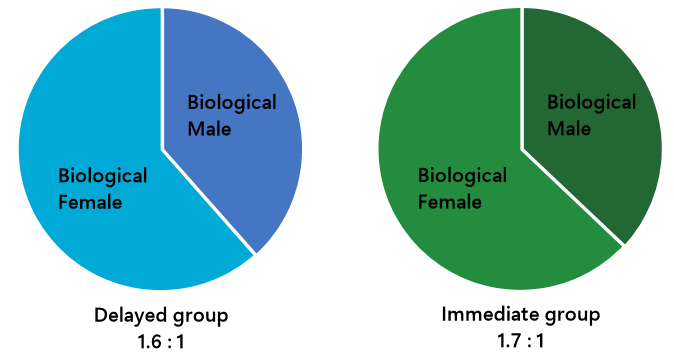

The ratio of biological males to females as follows in each group:

Additional details of the group such as living arrangements, education and extent of social transition were recorded for the group that began the study. These are given in Table 1 within the study, reproduced below.

What were the results?

The results section of the paper presents some detailed tables of data (see end) and highlights some specific observations.

Psychological Functioning

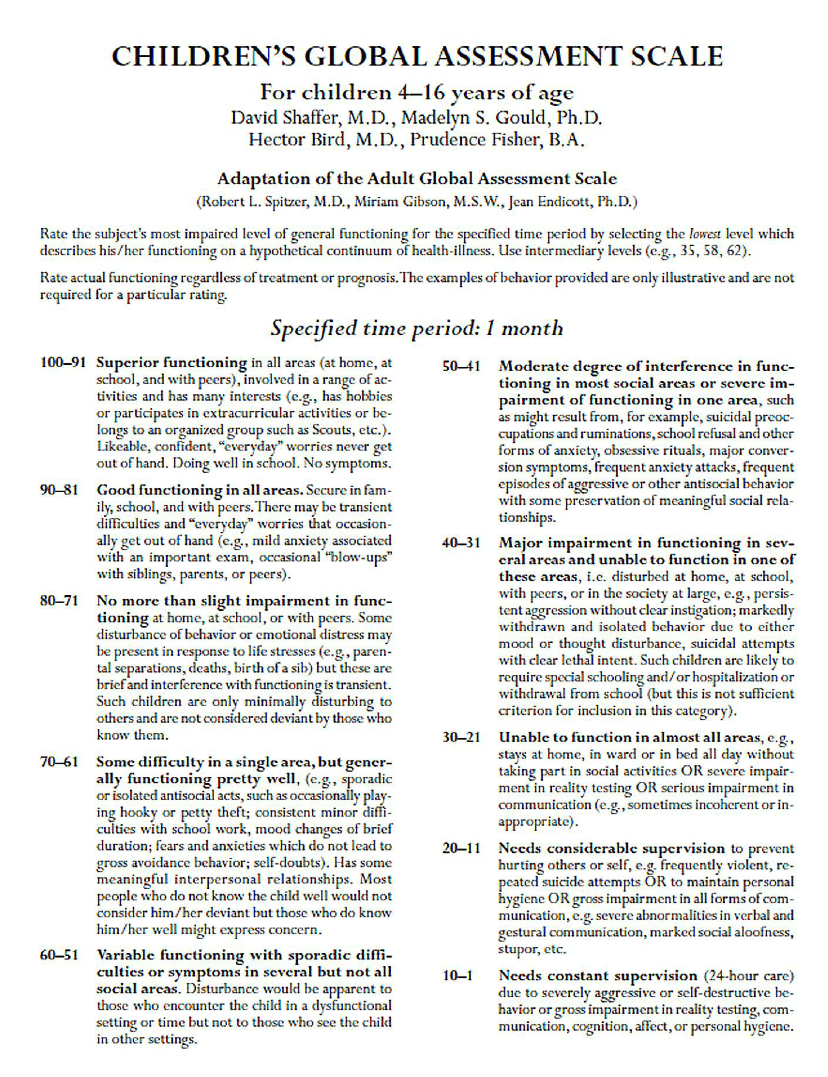

Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS)

This is a general assessment of mental health in a child, with the clinician assessing impact on the patient’s ability to function in day-to-day life. A higher number indicates better global functioning or a lower level of disturbance. The scale is not stated in the paper itself, but I have sourced and included a copy in Appendix A, for reference.

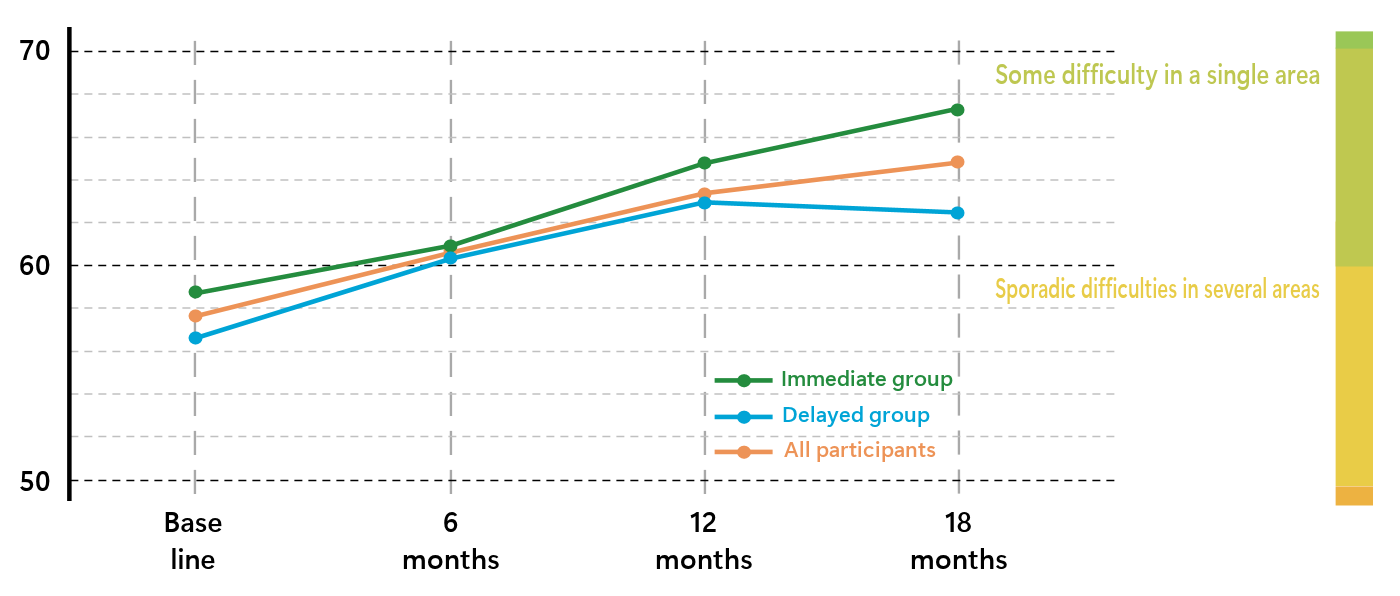

Results of these questionnaires were available for 35 participants in the “Immediate” group and 36 in the “Delayed” group. As can be seen in the following graph, an improvement was observed in the average scores for both groups, as well as overall:

Average CGAS scores (taken from Table 2):

The relevant score ranges (taken from Appendix A) are:

61-70 Some difficulty in a single area, but generally functioning pretty well

51-60 Variable functioning with sporadic difficulties

We can see that at the 12 month point, the delayed and immediate groups appear to diverge, based on the average scores, with the immediate group improving and the delayed group deteriorating slightly.

However, the authors note that “this difference failed to meet significance” - i.e. it was not statistically significant, and we therefore cannot say with confidence that there was any real difference between the groups. The authors suggest this may be due to small sample size.

Gender Dysphoria

Utrecht Gender Dysphoria Scale (UGDS)

This was used to measure adolescents’ gender dysphoria. This takes the form of a set of statements and the young person rates their agreement on a 5-point scale. A higher score indicates greater dysphoria. The overall score ranges from 12 to 60.

Results of these questionnaires were only published as part of the statistics on the group of 201 participants who proceeded beyond the initial assessment and diagnostic stage, shown at the bottom of Table 1. They show a high level of dysphoria for all groups at the outset:

As no figures are provided for later stages of the study, no conclusion can be drawn about the effects of treatment on this score. However, it does demonstrate that the participants had high levels of gender dysphoria before treatment.

What else did the authors discuss?

The authors state that the results indicate that “psychological support is associated with a better psychological functioning in [gender dysphoric] adolescents, especially if presenting psychological/psychiatric problems.” That is to say, over the period where psychotherapy was given, the psychological functioning of the participants improved.

They go on to say that “puberty suppression was associated with a further improvement in global functioning”, referencing the apparent diversion in CGAS scores mentioned above, though they also state that these were not statistically significant.

They discuss more generally that medical and surgical interventions are considered a necessary part of gender dysphoria in adults, and reference the Dutch Studies (references 2 & 9) to illustrate that adolescents may feel increased dysphoria at the onset of puberty.

They go on to say the following:

Therefore, in the pre-pubertal population, the suppression of puberty using [puberty blockers] is a fully reversible treatment which has the fundamental benefit for children of gaining time to reflect over their gender identity, have a real-life experience living as the other gender (i.e., in dress and behavior) and determine whether or not they desire transition.

References 12 (Cohen-Kettenis, 2008) and 13 (Cohen-Kettenis, 1997) are cited to qualify this statement.

They go on to make the case that blocking puberty assists in adolescents having a “smooth transition into their desired gender role” and that this contributes to improved psychological function, including “mood improvement and school integration” - again, citing the Dutch Studies.

The authors suggest a number of possible reasons why improvements are seen after as little as 6 months:

Addressing psychosocial problems in a timely way

Positive effects of knowing puberty suppression will eventually be given, even if not immediately

Beginning taking blockers may have a “psychological meaning” in itself to the participant

With the latter, they note that the data is too limited to draw a conclusion.

Some discussion is presented on the differences between biological males and females, and they note the following:

In the participants of this study, biological males began with significantly worse functioning than females, and reported more social difficulties (e.g. dropout from school)

Biological females, however, reported higher levels of gender dysphoria, which may be due to their higher age and therefore later stage of puberty

They therefore suggest that different approaches may be needed for the treatment of male and female adolescents. They also note that an updated Dutch model (reference 8) suggests beginning puberty suppression at 12 years old.

It is noted that, overall, the group of participants receiving both puberty blockers and therapy have psychological function that is “impossible to differentiate from a sample of peers”. They conclude that this provides additional evidence that the approach is effective in helping adolescents with gender dysphoria reach a satisfactory level of function.

Lastly, they discuss some limitations of the study:

Only a single measure of psychological functioning was used

The study sample was relatively small and came from a single clinic

Because of the study design, there are multiple possible explanations for the improvement seen in function - for example, getting older is often, in itself, associated with improved well-being

The absence of a control group prevents drawing direct conclusions about causality

The different questionnaires for males and females for UGDS means we cannot draw strong conclusions from comparisons between these two groups

They point out that ideally this would have been a blinded randomized controlled trial but note this is challenging to achieve. Reasons given are the difficulty in motivating adolescents to participate and possible ethical concerns over denying access to puberty suppression to those in the control group.

What did the authors conclude?

They state that:

The study “confirms the effectiveness of puberty suppression for [gender dysphoric] adolescents”

Along with the Dutch Studies (reference 2), the results “indicate that both psychological support and puberty suppression enable young [gender dysphoric] individuals to reach a psychosocial functioning comparable with peers.”

Conflicts of interest

The author(s) reported no conflicts of interest.

Full results tables

Please note: I do not own the rights to these images – they are taken from the paper itself. If you are one of the authors and would like me to take them down please get in touch.

References

The following list of references are cited by the study:

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th edition. Washington, DC; American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

de Vries AL, McGuire JK, Steensma T D, Wagenaar EC, Dorelciiers TA, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Young adult psychological outcome after puberty suppression and gender reassignment. Pediatrics 2014;134:696-704.

Colizzi M, Costa R, Pace V, Todarello O. Hormonal treatment reduces psychobiological distress in gender identity disorder, independently of attachment style. J Sex Med 2013;10:3049-58.

Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, Cohen-Kettenis P, DeCuypere G, Feldman J, Fraser L, Green J, Knudson G, Meyer WJ , Monstrey S, Adler RK, Brown GR, Devor AH, Ehrbar R, Ettner R, Eyler E, Garofalo R, Karasic DH, Lev AI, Mayer G, Meyer-Bahlburg H, Hall BP, Pfaefflin F, Rachlin K, Robinson B, Schechter LS, Tangpricha W, van Trotsenburg M, Vitale A, Winter S, Whittle S, Wylie KR, Zucker K. Standards of care (SOC) for the health of transsexual, transgender and gender nonconforming people, 7th version. Int J Transgender 2012;13:165-232.

Colizzi M, Costa R, Todarello O. Transsexual patients' psychiatric comorbidity and positive effect of cross-sex hormonal treatment on mental health: Results from a longitudinal study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014;36:65-73.

Colizzi M, Costa R, Todarello O. Dissociative symptoms in individuals with gender dysphoria: Is the elevated prevalence real? Psychiatry Res 2015;226:173-80.

Giordano S. Lives in a chiaroscuro. Should we suspend the puberty of children with gender identity disorder? J Med Ethics 2008;34:580-4.

Delemarre-van de Waal HA, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Clinical management of gender identity disorder in adolescents: A protocol on psychological and paediatric endocrinology aspects. Eur J Endocrinol 2006;155(suppl 1):S131-7.

De Vries AL, Steensma TD, Doreleijers TA, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Puberty suppression in adolescents with gender identity disorder: A prospective study. J Sex Med 2011;8:2276-83.

Kreukels BP, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Puberty suppression in gender identity disorder: The Amsterdam experience. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2011;7:366-72.

Di Ceglie D. Management and therapeutic aims With children and adolescents with gender identity disorders and their families. In: Di Ceglie D, Freedman D, eds. A stranger in my own body. Atypical gender identity development and mental health. London: Karnac; 1998:185-97.

Cohen-Kettenis PT, Delemarre-van de Waal HA, Gooren LJ. The treatment Of adolescent transsexuals: Changing insights. J Sex Med 2008;5:1892-7.

Cohen-Kettenis PT, van Goozen SHM. Sex reassignment of adolescent transsexuals: A follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36:263-71.

Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, Aluwahlia S. A Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS). Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983;40:1228-31.

Schorre BE, Vandvik TH. Global assessment of psychosocial functioning in child and adolescent psychiatry. A review of three unidimensional scales (CGAS, GAF, GAPD). Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004;13:273-86.

Lundh A, Forsman M, Serlachius E, Lichtenstein P, Landén M. Outcomes of child psychiatric treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2013;128:34-44.

Prince M, Glozier N , Sousa R, Dewey M. Measuring disability across physical, mental and cognitive disorders. In : Regier DA, Narrow WE, Kuhl FAA, Kupfer DJ, eds. The conceptual evolution of DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2011:189—227.

Sheldon KM, Kasser T. Getting Older, getting better? Personal striving and psychological maturity across the life span. Dev Psychol 2001;37:491-501.

Appendix A – CGAS Ratings

The original paper defining this scale is available here:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6639293/

As this is not available without a fee, I have used a copy that was reproduced here:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272824387_On_the_Children's_Global_Assessment_Scale