Parent Summary: Young Adult Psychological Outcome After Puberty Suppression and Gender Reassignment

Original authors: Annelou L.C. de Vries, MD, PhD, Jenifer K. McGuire, PhD, MPH, Thomas D. Steensma, PhD, Eva C.F. Wagenaar, MD, Theo A.H. Doreleijers, MD, PhD, and Peggy T. Cohen-Kettenis, PhD.

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2013-2958

What is a “Parent Summary”?

My aim in writing this is to present the information contained in the named study in a way that is accessible to a wide range of parents with trans kids, who may not be familiar with digging through formal scientific papers themselves.

I have deliberately avoided expressing any opinion on the content, though I may write other pieces that do in the future. But here, I am solely aiming to present what the authors say in more straightforward language. It’s not devoid of specialised terminology, but I have tried to make it so everything you need to understand the paper is in one place, with additional data in appendices where I think it is helpful.

I hope that reading this will allow parents to feel confident commenting on the content of a study in further discussion and to assist their child(ren) in making decisions about the treatments discussed.

The full version of the paper can be found at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25201798/ or searched online using the above DOI details1.

If you think I’ve missed or misrepresented anything here, please let me know, and I will endeavour to update this article.

Please note: there are certain parts of this study that I personally believe to have significant limitations or inaccuracies - I am not addressing this here, but rather in a separate document, to maintain clarity between my own opinion and recording what the papers themselves say in a clear manner.

What did this study investigate?

This study looked at a group of young adults who received puberty blockers as adolescents and went on to receive cross-sex hormones and gender reassignment surgery. It measured the effect of these treatments on feelings of gender dysphoria, on general psychological well-being, and examined subjective happiness / satisfaction with life after treatment.

When and where did it take place?

Participants were recruited at the Amsterdam Gender Identity Clinic between 2000 – 2008 and the results were published in 2014. It is the second of two studies that looked at this same group of adolescents, and these are sometimes referred to together as the Dutch study or studies.

How did it work?

Participants were assessed using questionnaires, filled out at three separate times:

Shortly after first attending the clinic, before taking puberty blockers

After taking puberty blockers for some time, before continuing to cross-sex hormones

At least one year after gender reassignment surgery

These were completed by the patient themselves, parents and clinicians. The differences between the sets of answers were used to assess the effects of the puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones and gender reassignment surgery.

On average, approximately 2 years elapsed between taking the first two questionnaires, and a further 4 years before the third.

Treatments differed between biological males and females, both in the types of cross-sex hormones administered and the surgery carried out:

Biological males / transwomen:

Vaginoplasty

Biological females / transmen:

Mastectomy

Hysterectomy with ovariectomy

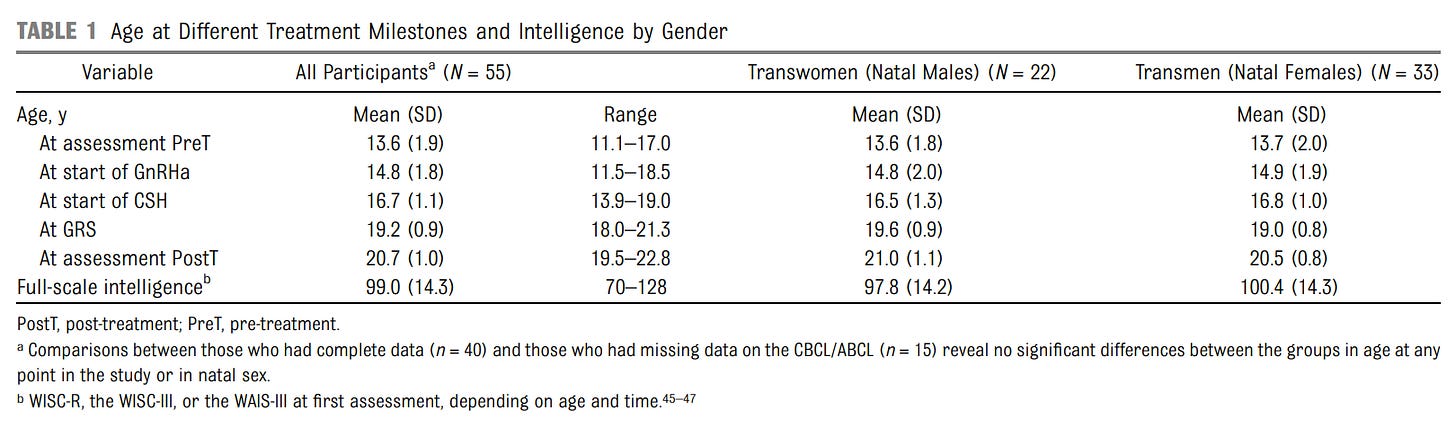

Who was included?

The participants were a subset of those who took part in the first study (see reference 16). Eligibility criteria for this were that adolescents would need to:

Be under 16 (those aged 16+ proceeded straight to cross-sex hormones)

Have persistently shown gender dysphoria since childhood

Live in a supportive environment

Have no serious psychiatric disorders that might interfere with assessment

e.g. the text highlights Autistic Spectrum Disorder as making this difficult

Have reached the initial stages of puberty (Tanner stage 2-3)

55 of the original 70 participants were assessed as part of this extended study. 22 were biological males / transwomen and 33 were biological females / transmen. Reasons are given in the paper why the remaining 15 were excluded:

Surgery was within the previous year – i.e. 1 year had not yet elapsed (6)

Refusal (2)

Not completing questionnaires (2)

Not being medically eligible for surgery – e.g. uncontrolled diabetes, obesity (3)

Dropping out of care (1)

1 transwoman died after vaginoplasty due to postsurgical necrotizing fasciitis

What were the results?

The results section of the paper presents some detailed tables of data (see end) and highlights some specific observations.

Gender Dysphoria and Body Satisfaction

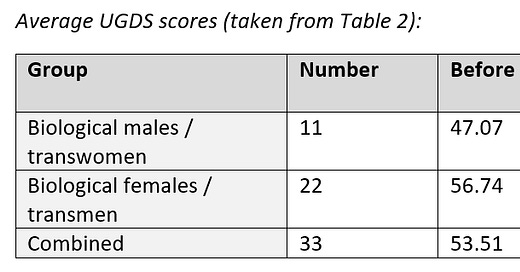

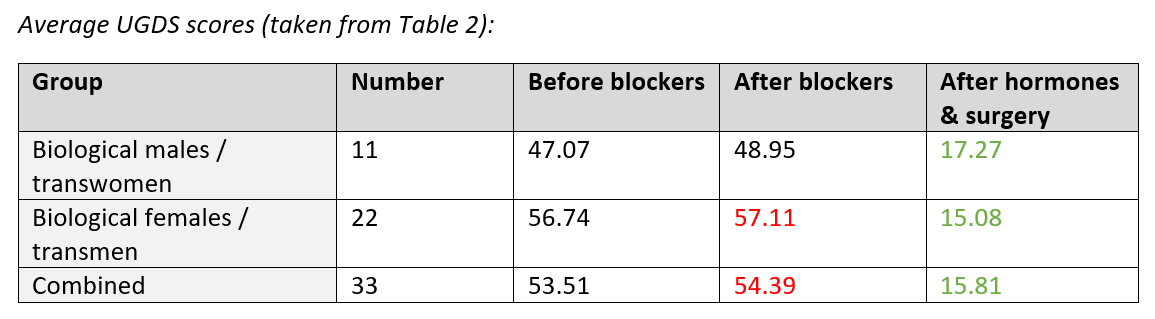

Utrecht Gender Dysphoria Scale (UGDS)

This was used to measure adolescents’ / young adults’ gender dysphoria. This takes the form of a set of statements and the young person rates their agreement on a 5-point scale. A higher score indicates greater dysphoria. The text gives an example statement of “I feel a continuous desire to be treated as a man/woman”.

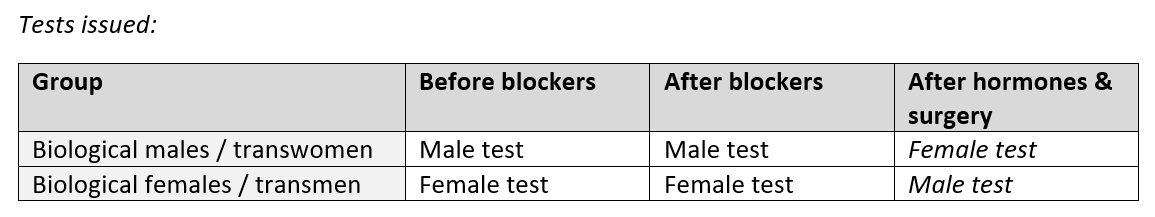

There are two different versions of the questionnaire, one for males and one for females, which the text says contain “mostly different items” and therefore cannot be compared directly with each other – e.g. to look for differences between males and females at a given point in time.

For the first two occasions when participants completed questionnaires, they filled out the version associated with their biological sex. However, for the third measurement, this was reversed and participants were given the version reflecting their adopted gender.

Results were available for 22 transwomen and 11 transmen, and these indicated that gender dysphoria continued while taking puberty blockers, but that the final results, after both cross-sex hormones and surgery, show a significant improvement:

Body Image Scale (BIS)

This asks the participant to rate 30 different body features on a 5-point scale, with a higher score indicating dissatisfaction. The results were grouped into three categories based on their relevance to gender: primary sex characteristics, secondary sex characteristics and neutral characteristics.

Again, there are male and female versions of the test, which the text notes are “identical except for the sexual body parts” and therefore allows for better comparison between groups. They were issued in the same way as the UGDS questionnaires, with participants being given the version reflecting their adopted gender for the third measurement (see above).

Results of these questionnaires were available for 45 participants and the authors note that although body image difficulties continued while taking blockers, they reduced significantly after hormones and surgery.

The authors note that transmen showed an increase in dysphoria relating to secondary and neutral characteristics after taking blockers, but that this decreased after taking hormones and receiving surgery.

A further effect that is reported is the observation that participants who were older when joining the study showed a greater level of body dissatisfaction at the outset, but that this gap narrowed over the course of treatment.

Psychological Functioning

Child/Adult Behaviour Checklist (CBCL/ABCL) and Youth/Adult Self-Report (YSR/ASR)

These questionnaires are completed by parents (CBCL) or the participant themselves and assess a range of general behavioural and emotional problems. Some questions were excluded due to the fact they are not suited to those experiencing gender dysphoria.

A score of more than 63 is considered to indicate a clinical issue, with higher scores indicating a more significant effect on function. Three scores were recorded – separate ratings for “internalizing” and “externalizing” behaviours, as well as a total score.

Results of these questionnaires were available for 40-43 participants and the authors remark that there is improvement over time by these measures, and that the percentage reporting a clinical issue drops significantly, representing an improvement in general behavioural and emotional problems.

The authors also note that on the externalizing measures, transmen showed a reduction whereas transwomen demonstrated no significant change (see Table 3 for details).

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

This is a multiple-choice questionnaire completed by the participant, and measures the level of depression on a numeric scale:

14 – 19: mild depression

20 – 28: moderate depression

29 or more: severe depression

Results of these questionnaires were available for 32 participants and the authors do not comment on the results, though they are shown in Table 3. The data listed indicates no statistically significant change2.

Trait Anger and Anxiety (TPI and STAI)

These are part of a larger set of tests (the Scales of the State-Trait Personality Inventory) and measure the tendency to respond with anxiety or anger to threatening or annoying situations. It presents 20 statements about how often these emotions are experienced and asks the adolescent to answer on a scale 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always).

Results of these questionnaires were available for 32 participants and the authors make limited comment on these, noting only that “transmen showed reduced anger, anxiety … whereas transwomen showed stable or slightly more [symptoms]” in this area. The data listed indicates that only the anger scores for transmen showed a statistically significant change (see Table 3).

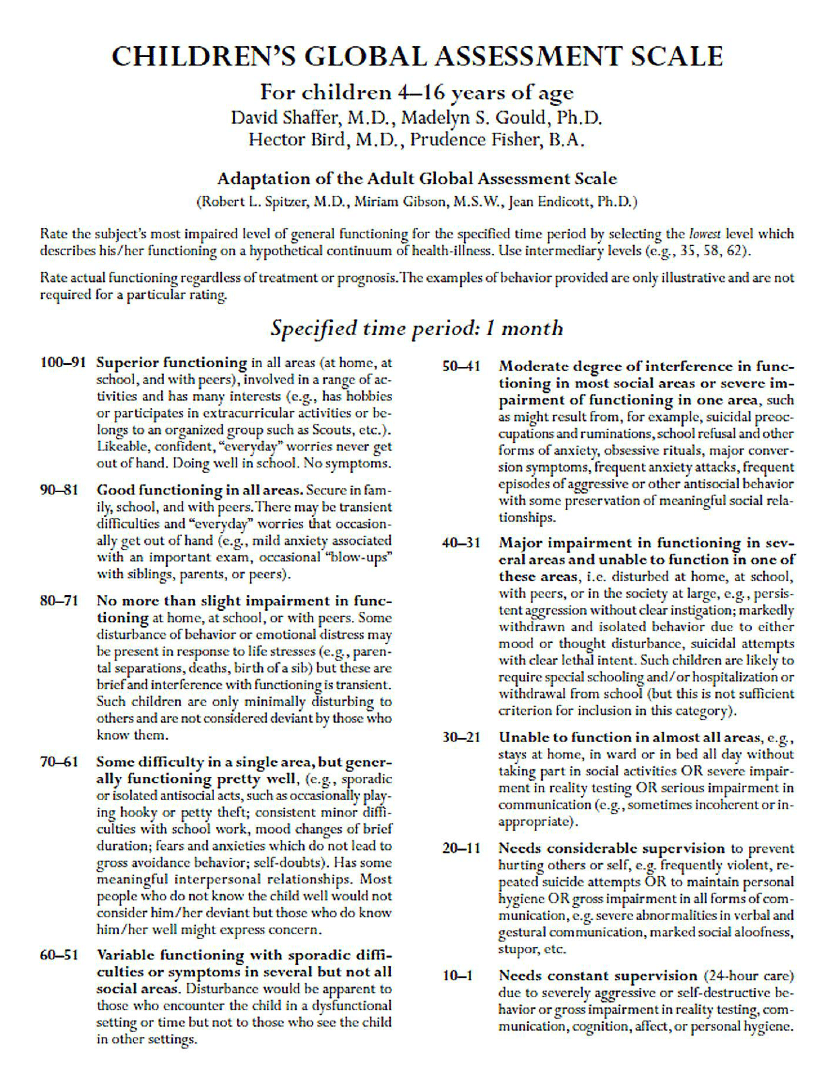

Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS)

This is a general assessment of mental health in a child, with the clinician assessing impact on the patient’s ability to function in day-to-day life. A higher number indicates better global functioning or a lower level of disturbance. The scale is not stated in the paper itself, but I have sourced and included a copy in Appendix A, for reference.

Results of these questionnaires were available for 32 participants and the authors note that these scores showed improvement over time – i.e. function became less disturbed.

The relevant score range (taken from Appendix A) is:

80-71 No more than slight impairment in functioning

Objective Well-Being

Participants were assessed at the end of the study by asking them about their lifestyle via a questionnaire. Where possible, responses were compared with values for the wider Dutch population. The authors reported that they were:

Slightly more likely to live with parents (67% vs 63%)

More likely to be pursuing higher education (58% vs 31%)

In addition, they note that:

Families were supportive: 95% of mothers, 80% of fathers, and 87% of siblings

79% reported having 3 or more friends

95% had received support from friends regarding their gender reassignment

89% reported never or seldom being called names or harassed

71% experienced social transitioning as easy

They were satisfied with their male (82%) and female peers (88%)

Subjective Well-Being

The authors state that none of the participants expressed regret during or after treatment. Satisfaction with the adopted gender was “high” and “no one reported being treated by others as someone of their assigned gender”. All reported they were very or fairly satisfied with their surgeries.

A number of questionnaires designed to assess quality of life were administered at the final stage, and the results compared with a wider group, for validation:

WHOQOL-BREF

This is measure developed by the World Health Organization, where participants answer on a 1-5 scale, with a higher number meaning better quality of life. 4 specific “domains” were covered: Physical Health, Psychological Health, Social Relationships, and Environment.

The Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS)

As the name suggests, this assesses the participants satisfaction with life. Participants answer on a 5–35 scale, with 20 being neutral.

Happiness Scale (SHS)

Participants answer on a 7-point scale, with higher scores reflecting greater happiness.

Across almost all results (see table 4) the answers were not statistically different to the wider group, with the exception of the WHOQOL Environment questions, where participants reported a higher quality of life.

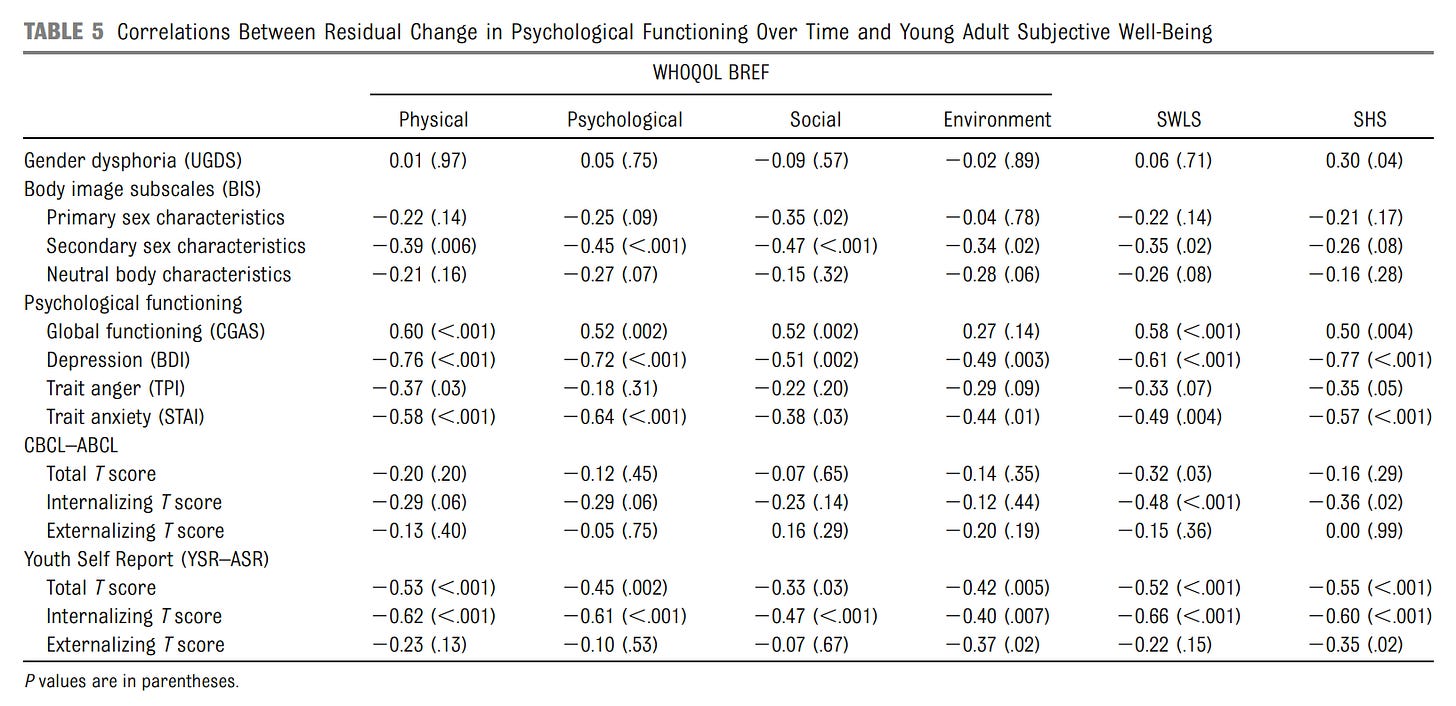

The authors also examined whether the change in the scores measured by the study correlated with the quality-of-life indicators. That is to say: did the participants who saw the biggest improvements over the course of treatment also report the best quality of life at the end?

The authors report that the following measures matched this pattern:

Secondary sex characteristics (BIS)

Global functioning (CGAS)

Depression (BDI)

Anger (TPI)

Anxiety (STAI)

Youth Self Report (YSR/ASR)

Of these, depression / BDI showed the strongest correlation. (See table 5 for full details)

What else did the authors discuss?

They note that this is the “first long-term evaluation of puberty suppression among transgender adolescents”.

They make the statement that, after treatment, gender dysphoria was “resolved” and highlight that the measures of well-being are generally comparable with peers.

It is reported that the effectiveness is in line with what is observed in studies of adults, citing references 35, 36 (see end).

They say that, although some studies in adults show dissatisfaction with surgery results (37, 38), all young adults in this study were “generally satisfied with their physical appearance and none regretted treatment.” The statement is made that “Puberty suppression had caused their bodies to not (further) develop contrary to their experienced gender”.

The authors highlight that psychological functioning improved throughout treatment and that, by the conclusion of the study, rates of clinical problems, quality of life and satisfaction with life are “comparable to same-age peers”.

They remark that the approach of a “multidisciplinary team with mental health professionals, physicians, and surgeons” allowed the gender dysphoric youths to “develop into well-functioning young adults”.

They highlight the contrast between the participants at the end of the trial and “transgender youth in community samples”, whom they characterise as having “high rates of mental health disorders, suicidality and self-harming behavior, and poor access to health services” (citing references 21, 22, 39, 40).

They note that the Environmental section of the WHO questionnaire includes ratings on items such as “access to health and social care” and “physical safety and security” and that the scores in this area may be attributed to the supportive home environments, as well as social and financial support, mentioning that the treatment they received is covered by health insurance.

They remark that, although both male and female participants benefitted, transwomen showed a greater improvement in body satisfaction, anger and anxiety.

They also mention that none of the transmen in the study had phalloplasty, either because of long waiting lists, or because of a desire to wait for improved surgical techniques. They suggest these concerns should be investigated further in additional studies.

They raise a number of limitations:

The study sample was small, and came from a single clinic

There was no assessment of physical side-effects

There is potential for bias in the way participants were selected from the group in the first study

On the subject of physical side effects, they mention a separate study (43) that followed up with the first participant in the study after 22 years and found no clinical signs of any negative impact on brain development, metabolic and endocrine parameters, or bone mineral density.

Finally, the authors discuss issues relating to age and consent, first noting that, especially in females, puberty often starts before age 12.

They highlight that, although there is evidence that childhood gender dysphoria continues into adolescence, “predicting individual persistence at a young age will always remain difficult”.

They remark that an age criterion of 16 for cross-hormone treatment may be problematic in transwomen, as growth in height will continue until this treatment begins.

The authors end this section by positing that “psychological maturity and the capacity to give full informed consent” may end up being the most important criteria in accessing these treatments.

What did the authors conclude?

This is the first study to provide evidence that “a treatment protocol including puberty suppression leads to improved psychological functioning of transgender adolescents”

The approach “contributes to a satisfactory objective and subjective well-being in young adulthood”

It is not just medical intervention that is important, but also:

A “comprehensive multidisciplinary approach” that attends to gender dysphoria and further well-being

A supportive environment

Conflicts of interest

The authors indicated there were none to disclose.

Full results tables & figures

Please note: I do not own the rights to these images – they are taken from the paper itself. If you are one of the authors and would like me to take them down please get in touch.

References

The following list of references are cited by the study:

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013

Cohen-Kettenis PT, van Goozen SH. Pubertal delay as an aid in diagnosis and treatment of a transsexual adolescent. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;7(4):246–248

Nakatsuka M. [Adolescents with gender identity disorder: reconsideration of the age limits for endocrine treatment and surgery.] Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi. 2012; 114(6):647–653

Zucker KJ, Bradley SJ, Owen-Anderson A, Singh D, Blanchard R, Bain J. Pubertyblocking hormonal therapy for adolescents with gender identity disorder: a descriptive clinical study. J Gay Lesbian Ment Health. 2010;15(1):58–82

Hewitt JK, Paul C, Kasiannan P, Grover SR, Newman LK, Warne GL. Hormone treatment of gender identity disorder in a cohort of children and adolescents. Med J Aust. 2012; 196(9):578–581

Olson J, Forbes C, Belzer M. Management of the transgender adolescent. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(2):171–176

Spack NP, Edwards-Leeper L, Feldman HA, et al. Children and adolescents with gender identity disorder referred to a pediatric medical center. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3): 418–425

Byne W, Bradley SJ, Coleman E, et al. Treatment of gender identity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(8):875–876

Adelson SL. Practice parameter on gay, lesbian, or bisexual sexual orientation, gender nonconformity, and gender discordance in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(9): 957–974

Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis P, Delemarrevan de Waal HA, et al. Endocrine treatment of transsexual persons: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(9):3132–3154

Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. Int J Transgenderism. 2012;13(4): 165–232

Cohen-Kettenis PT, Steensma TD, de Vries AL. Treatment of adolescents with gender dysphoria in the Netherlands. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2011;20(4):689–700

Thornton P, Silverman LA, Geffner ME, Neely EK, Gould E, Danoff TM. Review of outcomes after cessation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist treatment of girls with precocious puberty. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev Mar. 2014;11(3):306–317

Delemarre-van de Waal HA, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Clinical management of gender identity disorder in adolescents: a protocol on psychological and paediatric endocrinology aspects. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;155(suppl1):S131–S137

Steensma TD, Biemond R, Boer FD, CohenKettenis PT. Desisting and persisting gender dysphoria after childhood: a qualitative follow-up study. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;16(4):499–516

de Vries AL, Steensma TD, Doreleijers TA, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Puberty suppression in adolescents with gender identity disorder: a prospective follow-up study. J Sex Med. 2011;8(8):2276–2283

Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O’Connell KA. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF 8 DE VRIES et al Downloaded from by guest on October 7, 2016 quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(2): 299–310

Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49(1):71–75

Lyubomirsky S, Lepper HS. A measure of subjective happiness: preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc Indic Res. 1999;46(2):137–155

Koot HM. The study of quality of life: concepts and methods. In: Koot HM, Wallander JL, eds. Quality of Life in Child and Adolescent Illness: Concepts, Methods and Findings. London, UK: Harwood Academic Publishers; 2001:3–20

Carver PR, Yunger JL, Perry DG. Gender identity and adjustment in middle childhood. Sex Roles. 2003;49(3–4):95–109

Grossman AH, D’Augelli AR. Transgender youth: invisible and vulnerable. J Homosex. 2006;51(1):111–128

Steensma TD, Kreukels BP, Jurgensen M, Thyen U, De Vries AL, Cohen-Kettenis PT. The Urecht Gender Dysphoria Scale: a validation study. Arch Sex Behav. Provisionally accepted

Lindgren TW, Pauly IB. A body image scale for evaluating transsexuals. Arch Sex Behav. 1975;4:639–656

Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, et al. A children’s global assessment scale (CGAS). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40(11): 1228–1231

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996

Spielberger CD. Manual for the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1988

Spielberger CD, Gorssuch RL, Lushene PR, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the StateTrait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc; 1983

Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth SelfReport. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991

Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA Adult Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2003

Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1983

Cohen-Kettenis PT, Owen A, Kaijser VG, Bradley SJ, Zucker KJ. Demographic characteristics, social competence, and behavior problems in children with gender identity disorder: a cross-national, crossclinic comparative analysis. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2003;31(1):41–53

Statistics Netherlands. Landelijke Jeugdmonitor. In: Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Wetenschap en Sport, ed. Den Haag, Heerlen: Tuijtel, Hardinxveld-Giessendam; 2012

Arrindell WA, Heesink J, Feij JA. The Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS): appraisal with 1700 healthy young adults in The Netherlands. Pers Individ Dif. 1999;26(5): 815–826

Murad MH, Elamin MB, Garcia MZ, et al. Hormonal therapy and sex reassignment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of quality of life and psychosocial outcomes. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2010;72(2):214–231

Smith YL, Van Goozen SH, Kuiper AJ, CohenKettenis PT. Sex reassignment: outcomes and predictors of treatment for adolescent and adult transsexuals. Psychol Med. 2005; 35(1):89–99

Ross MW, Need JA. Effects of adequacy of gender reassignment surgery on psychological adjustment: a follow-up of fourteen male-to-female patients. Arch Sex Behav. 1989;18(2):145–153

Lawrence AA. Factors associated with satisfaction or regret following male-to-female sex reassignment surgery. Arch Sex Behav. 2003;32(4):299–315

Grossman AH, D’Augelli AR. Transgender youth and life-threatening behaviors. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2007;37(5):527–537

Garofalo R, Deleon J, Osmer E, Doll M, Harper GW. Overlooked, misunderstood and at-risk: exploring the lives and HIV risk of ethnic minority male-to-female transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(3): 230–236

Toomey RB, Ryan C, Diaz RM, Card NA, Russell ST. Gender-nonconforming lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: school victimization and young adult psychosocial adjustment. Dev Psychol. 2010;46 (6):1580–1589

McGuire JK, Anderson CR, Toomey RB, Russell ST. School climate for transgender youth: a mixed method investigation of student experiences and school responses. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39(10): 1175–1188

Cohen-Kettenis PT, Schagen SE, Steensma TD, de Vries AL, Delemarre-van de Waal HA. Puberty suppression in a gender-dysphoric adolescent: a 22-year follow-up. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;40(4):843–847

Steensma TD, McGuire JK, Kreukels BP, Beekman AJ, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Factors associated with desistence and persistence of childhood gender dysphoria: a quantitative follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(6):582–590

Kreukels BP, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Puberty suppression in gender identity disorder: the Amsterdam experience. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7(8):466–472

Wechsler D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children: Manual. 3rd ed. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997

Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-III). 3rd ed. Dutch version. Lisse, Netherlands: Swets and Zetlinger; 1997

Wechsler D, Kort W, Compaan EL, Bleichrodt N, Resing WCM, Schittkatte M. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-III). 3rd ed. Lisse, Netherlands: Swets and Zettlinger; 2002

Appendix A – CGAS Ratings

The original paper defining this scale is available here:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6639293/

As this is not available without a fee, I have used a copy that was reproduced here:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272824387_On_the_Children's_Global_Assessment_Scale

When looking up scientific papers online, you may often find you only have access to the abstract, but you can usually have some luck finding the full paper online by googling something like “full text” along with the full name of the paper.

When commenting on statistical significance, this is based on the t test value, taking the commonly accepted threshold of less than 0.05 as being statistically significant.

What was the average age of onset of gender dysphoria in this paper? Clearly before puberty - in this study (different group) it was 8 years old https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/doi/10.1542/peds.2021-056082/186992/Gender-Identity-5-Years-After-Social-Transition. I am sorry, at that age most of these kids probably believed Santa Claus is real...

I’ll just comment here - this study lacks appropriate controls. The children appear to be statistically indistinguishable from the overall population at the last time point, despite receiving exceptional support and medical care their entire lives. But is the background population the right control group? How many dysphoric children resolved on their own with similar supporting environments? And if you received such excellent support wouldn’t you expect other measures of well being to be higher?

And of course, it is not clear what these results have to do with the current wave of post pubescent kids who suddenly “discover” they are actually the other gender.